The results encompass racism, opportunity and the desire for a larger middle class

This is the first installment in a two-part series. Go here to read the next installment.

In 24 years, Marisa Bartley had never heard the “n-word” hurled at her by a white person. One day, it hung in the air in the lobby of a Verona bank, where she worked as a branch manager. A disgruntled male customer stood on the other end with an enraged expression.“It was the n-word, face-to-face,” Bartley recalled with an uncomfortable chuckle. “Of course I was stunned to hear it, but I felt sad for him; he had no idea how the world was rapidly changing around him.”

Nigerian immigrant Rufus Idris recalls a swarm of Swissvale police cars surrounding his vehicle after an officer pulled him over for allegedly running a stop sign. He was on his way home after giving a lecture at Carnegie Mellon University when police stopped him. One white officer laughed as he saw Idris dressed in his African attire.

“The way I was dressed was funny to them,” he said. “An officer handed me a ticket. I asked, ‘What is this for?’ He said, ‘You ran a stop sign?’ I questioned him about which stop sign, and he said it was a few stop signs back down the road. I asked, ‘Why didn’t you stop me then?’ He didn’t have an answer.”

Evan Frazier described an experience the first week back home in Pittsburgh in 1992 after graduating from Cornell University. “I was pumping gas in a suit and tie, just like I’m wearing now, and I clearly remember a woman coming up to me and saying, ‘Excuse me, can you pump this gas for me,’ as if I was an employee. I said, ‘No, I actually don’t work here.’ She said, ‘Oh, sorry,’ like it bothered her.” That same week, someone had mistaken him for a fast-food restaurant manager while informing him of a bathroom mess.

These are just a few examples of frustrations experienced by African Americans new to Pittsburgh and making their way in this city, now known internationally as a destination on the rise. Their experiences raise the question: Is Pittsburgh meeting its prideful “most livable city” label? Or is it only the most livable city for white people?

In the wake of the Pittsburgh Regional Quality of Life Survey, which shows major quality-of-life differences between African Americans and other races in Pittsburgh, we interviewed several African Americans in Pittsburgh, most of whom were recent transplants. We asked them about their experiences as newcomers to Pittsburgh and how life here compares with what they had experienced in other cities.

The negatives are striking: Racism is still prevalent here, they said. But the positives are encouraging: Many agreed Pittsburgh is a place where it’s easy to be a pioneer, where people can make a name for themselves if they so choose. It’s also a place where people can jump into various circles and act as change agents.

There’s the recent creation of Vibrant Pittsburgh, a nonprofit organization dedicated to growing the diversity of the region and its workforce. “I think Vibrant Pittsburgh being created was one of the best things this city has done,” said Jeanine Blackburn, a lifelong Pittsburgher and president of the National Black MBA Association’s Pittsburgh Chapter. “The team clearly is passionate about bringing people together and helping transplants navigate the region.”

The group’s president, Melanie Harrington, is a transplant who moved here two years ago after living in Atlanta and Los Angeles. Harrington, who is black, chose to live downtown. “I, for one, like it here,” she said. “I have a network of friends —a group of people who went out of their way to help integrate me into the Pittsburgh community. If you compare Pittsburgh to that place you left, you’re not letting go in order to appreciate what Pittsburgh has. When you move into any new place, you need to let go a little bit of the place you came from in order to immerse yourself in your new place and space. That is what I did.”

Candi Castleberry-Singleton, 46, moved to Pittsburgh about five years ago to take a job as UPMC’s first chief inclusion and diversity officer. She grew up in Los Angeles, with degrees from UC Berkeley and Pepperdine University, and also lived in Chicago and Philadelphia.At UPMC, Castleberry-Singleton’s goal is to promote a culture of inclusion in the workforce and in the healthcare practice. As a black woman, she described two watershed moments since moving here that helped shape her belief of what Pittsburgh is and what it could be.

The first is distressing. When Castleberry-Singleton and her husband arrived here, they felt discriminated against by the staff of a downtown apartment building. On a Saturday afternoon, the staff failed to answer the door’s buzzer several times. The couple went to a nearby deli for lunch and called the building from their cell phone, being assured they would be let in. They returned and rang the buzzer again. No one came to the door.

“I wanted to believe that they were busy working inside,” she said. “But it was a slow day and there were four people in the office.”

The staff told her they had no two-bedroom apartments to rent. Eventually, Castleberry-Singleton learned through a white colleague who lived in the building that a vacant two-bedroom apartment was available. Then she learned the building also kept a waiting list for potential tenants.

“When I was there, no one told us about a waiting list,” she said. “The staff was always friendly to me over the phone. But it was a different story when I showed up in person. More than anything, I was disappointed in this new place I was moving to.”

In the end, the couple still settled downtown, but in another building.

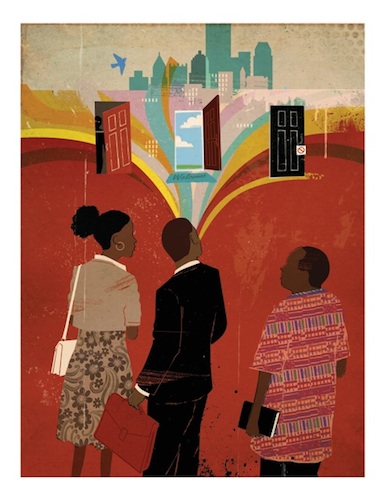

Illustration by Dan Marsula

Castleberry-Singleton’s other Pittsburgh moment came shortly after the Pittsburgh Steelers won Super Bowl XLIII in 2009. She stood at the top of an escalator inside the UPMC building on Grant Street, snapping photos of the fans.

“I saw black people and white people and people of all different kind of faiths,” she said. “It gave me chills. I thought, ‘If people could come together like this, sober for the most part, to celebrate their team, then this city has much more potential.’ I just had to help find a way to connect this thing.”

As a result, Castleberry-Singleton founded the Dignity and Respect Campaign which is dedicated to promoting inclusion through behavioral and organizational change in communities, schools and corporations.“I want to work in a place where I feel like I can be me,” she said. “I want to go home and live in a community where I am not going to feel isolated. I want to be able to have things to do in the community that allow me to celebrate my own culture and to learn about other cultures. That’s what we’re aiming for.”

But that’s been a tall order for one successful black Pittsburgh business owner, who often returns to Washington, D.C., where he got his degree from Georgetown University. The man, who requested anonymity, said the African American middle class in Pittsburgh is so scant that he travels back to Washington, D.C., to go on dates.

Recent U.S. Census figures back him up—Pittsburgh has the highest poverty rate among working-age African Americans of the 40 largest regions in the country.

The businessman said the gulf between the haves and have-nots in the black community is difficult to overcome. “You do not have neighborhoods where you have a critical mass of middle-class black people. If you want your kids to have a good education, you have to make the choice to either live in a community like Fox Chapel or Mt. Lebanon, where there are hardly any kids in class that look like them. Or you pay a lot of money to go to independent schools, where you have a few more kids that look like them, but pretty much everybody coming from some measure of economic privilege.”

The businessman, who grew up in a Southern city and spent several years in Washington, D.C., has lived in Pittsburgh for 15 years and said he still feels like a stranger. “I’m adjusted to seeing African Americans in substantial leadership roles, and that’s not welcome here. I feel tolerated, but not welcome.”

He described a sinking feeling every time he returns to Pittsburgh from another city’s airport. “Coming back is painful every time. I get in the boarding area and see that I am outnumbered again. People look past you; they don’t acknowledge you. They don’t engage you. For me, it’s like ‘Well, back to Pittsburgh. Get your Pittsburgh game on.’ ”

It’s a sentiment shared by Pittsburgh City Councilman R. Daniel Lavelle, who has spent most of his life here but travels often.

“If I get off the plane in a place like Charlotte, it’s so diverse: black, white, Indian, Asian,” he said. “Whenever I come back home and land, I say to myself: ‘Wow, it’s so white.’ It is very startling and in your face.”

Evan Frazier, who described the gas station incident, chose to return home to Pittsburgh after Cornell, and received a master’s degree from Carnegie Mellon University. He is now senior vice president of community affairs for Highmark Inc. And he’s happy here with his wife and three children.

“I recognize that while we’re not perfect, we have a lot of things to offer,” said Frazier, 42. “In particular, I found that Pittsburgh, as a family town, is tremendous.”He also recognizes the city’s shortcomings. “There’s not the same black middle class neighborhood that you might have in other cities. And we, as a region, cannot ignore the poverty of many African Americans that are already here. We have to work deliberately in corporate Pittsburgh to make change there.” Lavelle offered this blunt assessment: “Most livable? Not for black people. Pittsburgh is much more segregated than the majority of cities I’ve been to. The recent census validated some of that.”

He describes segregation by geography that permeates the region. “Let’s say you’re driving down Penn Avenue. There’s generally the white side and the black side of Point Breeze. Our communities are still pretty much bunched that way.”

Still, Lavelle calls Pittsburgh home and sees positive signs of change. “I often tell a lot of younger minorities that are looking to move here that we are on the uptake and you have an opportunity to make your mark if you come here. We’re not Atlanta, but you have a wonderful opportunity to kick in any door that you want and blaze a path for yourself.”

Vanessa German, a 36-year-old artist, took that mantra to heart when she moved to Pittsburgh 10 years ago from Los Angeles. German, who has become a well-known sculptor, poet and performance artist in the area, is very happy in Pittsburgh. The Pittsburgh Center for the Arts named her its 2012 Emerging Artist of the Year.

“I am inspired by Pittsburgh; I relish the adventure of it,” said German, who lives in Homewood. “I’m a big fish in a small pond here, and it’s great. I do something that no one else around here is doing. In my mind, I’m exactly where I’m supposed to be. There’s a big foundation community here and the opportunity to get a lot of support.”

Nonetheless, she has had her share of unpleasant incidents. She originally settled with her parents in Monroeville before moving to Homewood. “It was interesting to see how the police treated us in Monroeville,” she said. During one incident, her father’s pickup truck got stuck in the mud on their property. “We’re out of the truck, trying to push it, and all of a sudden there are six cop cars there. They were blocking our driveway and told us, ‘The owners aren’t going to like you tearing up this lot with your truck.’ We told them we were the owners and they asked us to prove that we lived there.”

On another occasion, German and her family stepped outside to see a car accident that ended on their front lawn. The police arrived and told them to leave the crime scene. “We told them it was our property,” she said. “They didn’t believe us at first.” German shrugged it off. “Moving to a place where there are a lot of white people and I’m different is not that hard. For me, hard is being homeless and ducking behind bushes for shelter and sleeping outside.”

Shannon Finley, a 23-year-old Spanish teacher at Pittsburgh’s Sterrett Classical Academy and Phillips Elementary, described Pittsburgh as “the perfect fit” for her. She grew up 40 miles outside of Philadelphia, in Douglassville, and attended Albright College in Reading before transferring to the University of Pittsburgh. She spent a lot of time in Philadelphia and found Pittsburgh to be much more welcoming, even as a young African American.

“It’s a small town when compared to Philly, but I am OK with that,” said Finley, who completed her undergraduate and master’s degrees at Pitt, and has lived here for four years. “I think by default, I am going to be meeting younger, diverse and more open-minded people here, since I just got out of college. This place is much friendlier than Philadelphia, in my mind.”Surprisingly, Finley said many younger African Americans are the hardest for her to connect with. She often jogs through Homewood and Garfield and says she always has to initiate a “hello” with young black people. “I wonder if that’s a cultural thing here, I’m not sure,” she said. “Older people are welcoming and warm. Not as much with younger African Americans.”Finley also said she has no problem dating in Pittsburgh. “I haven’t had a problem dating people of all races. I don’t limit myself to one specific race. But it probably is a little more difficult if you are looking to date a black man who has an education beyond high school. That’s not just in Pittsburgh, though.”

However, in Pittsburgh’s suburbs Finley described a different vibe. “In the suburbs, you quickly realize you are black. But I think it’s like that all over the country. I was in Cranberry, and it reminded me of the neighborhood I grew up in. I definitely had a feeling that I was standing out as a black person and might be perceived in a different way.” Rufus Idris, who said he was unfairly ticketed by Swissvale police officers, agrees with Lavelle that Pittsburgh is a land of opportunity of sorts. Idris, 31, is originally from Nigeria. He lived in Providence, R.I., before moving to Pittsburgh seven years ago.

He is executive director of the Christian Evangelistic Economic Development, a nonprofit organization providing microenterprise and technical assistance to businesses in the region. He also co-founded The Union of African Communities in Southwestern Pennsylvania.“A lot of Pittsburgh people don’t have a clear understanding of who immigrants are,” Idris said. “We need to tell our own story and emphasize the values we can bring to the region and how we can help support the economic growth of the region itself.”

The African union he founded now represents 26 countries and recently celebrated its fourth annual heritage festival in Highland Park. Each year the festival travels to a different community.“We had free food, dance performances, crafting, music and more,” he said. “People came and realized how nice it was. Not to sound funny, but I think they started to realize that these immigrants aren’t here to commit crimes and harass people. Of course, when I travel to Washington, D.C., or New York, I walk down the street and see lots of foreign people,” Idris said. “People live with that every day. Our population is not that large, but it’s not necessarily the residents’ fault. We need to help expose them to new things.”

Marisa Bartley, the branch manager who was called a racial slur in a Verona bank, transferred to a downtown office. Now 29, she lives on the city’s North Side and also serves as president of the Urban League Young Professionals of Greater Pittsburgh. She acknowledged Pittsburgh’s issues with racism and diversity but is resolute that the city has also been very good to her.“What I tell people is that Pittsburgh is what you make of it,” said Bartley, who grew up near Philadelphia in Media, Pa. “From an African American perspective, it is an amazing place for young people hungry for change. We need people who are serious about doing the work and not serious about window dressing.”

Bartley said the key to the region’s success is going to center on making diversity sustainable.“Right now, I don’t think it is,” she said. “Arts and culture is great, but you have to think about the young professional demographic of African Americans. We have one of the highest concentrations of working poor African Americans in the country. It’s easy to miss because they are pushed out into the city’s outskirts.”

UPMC’s Castleberry-Singleton agreed. “When you’re talking about Chicago, you are talking about a city,” she said. “When you are talking about Pittsburgh, you are talking about someone’s home. Pittsburghers love Pittsburgh.

“But for the economy to truly grow, the city and region have to find a way to be more welcoming, not just friendly. Many times, people who move into Pittsburgh are moving into a neighborhood where people have longstanding relationships with each other. That distinguishes the difference between people being friendly and people being welcoming to newcomers. I think in many ways the region has already transformed, and it has amazing potential to be a mecca for people to relocate.”

This is the first installment in a two-part series. Go here to read the next installment.