The dynamics of minority workers and their role in the southwestern Pennsylvania labor force are complex, broad in scope and not fully understood. And for decades, those who’ve tried to diversify the workforce have found it largely resistant to change. Data that depict a southwestern Pennsylvania labor force conspicuously low in minority workers lend little insight as to the precise reasons why that continues to be the case. However, research on workforce inequality, local experience and observations and other evidence suggest several possibilities.

Among them is whether levels of education and skills align with requirements of available jobs.

Employers and economic development organizations, for example, express concern over what they see as a growing shortage of workers able to fill high-skill professions, such as engineering. And the concern extends to the supply of workers able to step into middle-skill jobs, which require a high school education and some additional training, but usually not a college degree.

The issue is particularly acute in southwestern Pennsylvania, which has undergone a profound shift from an industrial economy and the blue collar jobs that had sustained generations to an economy that rewards workers trained for vastly different occupations in medicine, research, education, finance, technology and energy. And it hasn’t been kind to those whose skills, training and opportunities have not kept pace, particularly long-time minority workers and their families whose livelihoods and experience were tied to industries in decline.

Whether minorities have reliable transportation to and from training and jobs is another possible factor contributing to the lack of diversity in the region’s workforce, particularly when the job opportunities lie beyond the reach of public transit. A Brookings Institute study reports, for example, that the migration of jobs away from urban central business districts isolates minorities from those jobs much more so than whites, exacerbating racial inequalities.

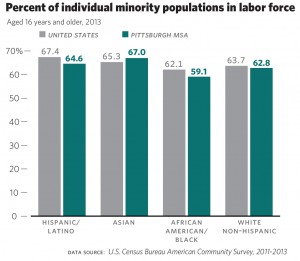

Another is the demographics of southwestern Pennsylvania, which find minority and foreign-born residents claiming a smaller share of the general population than in any other Pittsburgh Today benchmark region, offering employers a shallower pool of those workers to draw from.

And the lack of diversity in the workforce itself tends to limit the job options of minorities, denying them the awareness of a wide range of occupations, what they’d do in those jobs, the skills they need and a network of people they know who are working in those fields.

“Connection to jobs is no minor point,”says Larry Davis, dean of the School of Social Work and director of the Center on Race and Social Problems at the University of Pittsburgh. “So much of what happens to us in life has to do with social capital. How are they going to find someone to teach them how to lay concrete or know someone with a nephew who can help them get a job doing that? They aren’t, because they are out of the network.

“I had a kid in my house the other day who had never seen a black lawyer. This is 2015. This kid was 18 years old. You don’t know what’s possible if you never see it. And it’s hard to be what you’ve never seen.”

Rayfield Lucas spent most of his working life in maintenance and warehouse jobs that offered few opportunities for growth before he decided to retool for the shale gas industry at the age of 47. “That was what I knew and it was convenient for me,” he says.

“We know from research and data that to imagine new careers and pursue them, it is critical to get a realistic preview of what life could be like in those careers,” says Vera Krekanova Krofcheck, director of strategy and research with the Three Rivers Workforce Investment Board, which directs $12 million a year in workforce development funding. “But we don’t have enough of the cross pollination across careers that happens more organically when you have diversity in the workplace.”

Searching for Solutions

Corporate human resource departments, economic development groups, foundations and others have long worked to diversify the region’s workforce in various ways, largely with individual programs and investments.

Recent, more coordinated efforts led by organizations such as Vibrant Pittsburgh, the Allegheny Conference on Community Development and Global Pittsburgh have focused on attracting and keeping minority workers from outside the region to help ease concerns of a manpower crisis in industries such as manufacturing, energy, finance and technology.

Of particular interest has been attracting foreign-born workers. As a group, the region’s foreign-born residents are among the most highly educated in the nation. But they are few in number, claiming only 3.8 percent of the region’s population. By comparison, foreign-born residents account for nearly 13 percent of the U.S. population as a whole. Meanwhile, conditions for convincing more foreign-born workers to settle in southwestern Pennsylvania have improved with growth in job opportunities and the continued strength of local universities.

¡Hola Pittsburgh! is an example of a recent effort to grow the region’s minority population and workforce. The public private partnership of businesses, government, nonprofit groups and Latino community leaders was created to help make southwestern Pennsylvania a more attractive place to live and work for Latinos, including both foreign-born and native U.S. citizens. Last year, its efforts focused on talent from the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico.

“The attraction piece is an awareness issue – making people aware of the opportunities and quality of life in Pittsburgh,”says Dennis Yablonsky, chief executive officer of the Allegheny Conference on Community Development. “We have a large number of international and minority college students. The more we can do to keep them here after they graduate, the better off we’re going to be. And there are populations on the move. Puerto Rico is an example where a lack of economic opportunity causes young people to leave the island every year. They’re educated. They speak English. And they are trained in our areas of need.”

How to increase the share of the regional workforce and the number of fulfilling jobs held by minorities with generations of history in southwestern Pennsylvania is a complex question the region has not been able to answer.

Several examples of efforts to address a piece of the puzzle can be found throughout the region.

Lucas broke into the shale gas industry with training from the region’s ShaleNET program at Westmoreland County Community College, where in the first eight months of 2014 nearly one in five roustabouttraining graduates were minority students. The Three Rivers Workforce Investment Board finds that a significant share of those who use placement services, such as CareerLinks, are minority jobseekers, although such services are not specific to them.

More targeted efforts include programs run by The Urban League intended to promote scientific, technology, engineering and mathematics education among minority students. At Point Park University, the Urban Accounting Initiative goes into middle schools and high schools and organizes summer programs to expose minority and female students to a field that few know about and even fewer enter.

“For these students to get meaningful employment and join the middle class they’re going to need to be in a white collar profession. And it’s all about whether there is anyone who looks like me that I can relate to who can show me the possibilities. Just not enough of that has been done,” says Edward Scott, who heads the Urban Accounting Initiative as the George Rowland White Endowed Professor in Accounting and Finance at Point Park University.

Such efforts are small in scale compared to the breadth of the challenge of building the capacity of minorities to succeed, which includes addressing issues ranging from education and poverty to transportation, neighborhood disinvestment and attitudes about race and ethnicity.

“We talk about wanting diversity, wanting minorities to come to Pittsburgh. That’s fine,”says Pitt’s Davis. “But the bottom line is: Pittsburgh needs to invest more in the capacity of its own people to take advantage of opportunities that are being created – in its black population, to be candid. You can’t expect anything to grow if you don’t plant the seeds and do the plowing.”

More work needs to be done to identify the characteristics of the southwestern Pennsylvania labor force that prevent minority workers from claiming a larger share of the jobs and wealth the economy has to offer, as they do in much greater numbers in metropolitan regions from Atlanta to Cleveland. A deeper understanding of the factors behind wage discrepancies, for example, and those driving low minority hiring in several better-paying industries remains a work in progress.

What is clear is that the issue is pervasive and deeply entrenched, suggesting that a coordinated, community-wide strategy involving regional leaders and disparate stakeholders over the long term is needed to make southwestern Pennsylvania a place better known for diversity and inclusion than the lack of it.