Pittsburgh’s slowly emerging land bank

One year after the City of Pittsburgh passed an ordinance enabling it to create a land bank, the new tool for addressing vacant and blighted properties on a large scale remains a work in progress. Whenever it is ready, it will have plenty of work to do.

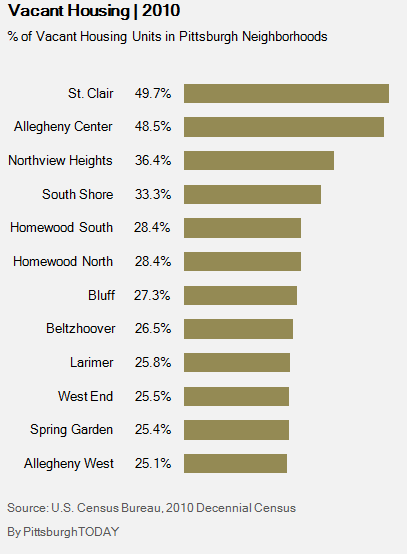

Some 12.8 percent of housing in the city is vacant, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2010 decennial census. But in more than 30 neighborhoods, 18 percent or more of the housing is vacant.

Such pockets of high concentrations of vacancy have the potential to destabilize neighborhoods, prevent tax revenue from flowing into the communities and lower property values.

Widespread problem

City neighborhoods with higher than 18 percent vacant housing units include Marshall-Shadeland, Hays, Upper Hill and the Strip District. Neighborhoods such as Hazelwood, Garfield and Manchester have more than 20 percent vacant housing, according to census data.

The three neighborhoods with the highest rates of vacant housing in the city are St. Clair, where 49.7 percent of housing is vacant; Allegheny Center where the rate is 48.5 percent; and Northview Heights, where 36.4 percent of houses stand vacant.

Why blighted properties remain has a lot to do with how difficult and lengthy it is to clear title on the properties, according to Sabina Deitrick, co-director of the Urban and Regional Analysis Program at the University of Pittsburgh’s University Center for Social and Urban Research. “Then, it’s putting together a collection of properties that can be meaningful. In old cities, there’s a lot of single properties, but then you end up with a dot map that’s not going to help redevelopment, so [you need to] put together contiguous problem properties.”

Land banks emerge

A dysfunctional housing market typifies neighborhoods with high concentrations of vacant problematic properties and signals the need for an outside intervention. Land banks have become an increasingly popular tool for addressing vacancy and helping to turn around such markets.

“Land banks are needed where there’s not other investment. The neighborhoods where the market is working you don’t have to worry about vacant property. Land banks are when buildings don’t have value,” said Deitrick.

Land banking is the most potent legal tool yet for acquiring large numbers of problem properties and setting them on a path toward redevelopment by selling them, renovating them or demolishing them and repurposing the property.

“Land banking allows you to look at different places and effect change at scale. You can have the best plans in the world, if you don’t have site control it doesn’t matter,” said Bethany Davidson, Neighborhood Policy Director, Pittsburgh Community Reinvestment Group.

A 2012 state law opened the door to local governments, community development organizations and others to create land banks. The City of Pittsburgh passed an ordinance to establish a land bank in April 2014.

Slow to develop

The city’s land bank hasn’t acquired a single property and still has a way to go before it does. It is still in the process of organizing, which includes seating a full board of appointees. Then the work begins to define its powers and role and how it will function.

“The work that will happen in the land bank is a lot of legal work in terms of policies and procedures understanding how the land bank will operate and how it fits in with the overall vision of how we restructure how we recycle property,” said Kevin Acklin, chief of staff to the mayor and chief development officer, City of Pittsburgh.

It might be another year before the land bank is ready to begin putting together a portfolio of vacant, tax-delinquent properties available to those who want to return them to productive use.

Community development groups are looking ahead to a future with a streamlined land recycling process in the city and land banking expedites a new path for a vacant and derelict properties. “I think people are cautiously optimistic that a system shift toward proactive land recycling will make this at least a little easier,” said Davidson. “Groups are a little more hopeful at the same time. This has widely been recognized as a key component in true neighborhood revitalization for a long time.”